While the US has successfully led a united Western front in pushing back against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Washington has not been as effective in its policies on Iran, China and the Horn of Africa.

Source: Al Arabiya

Shortly before being confirmed as the top US diplomat last year, Antony Blinken told lawmakers that he would work to revive what he said was damaged American diplomacy by forming a united front to counter Iran, China and Russia.

But US diplomats and sources close to several former and current officials have said there is growing frustration within the State Department due to the centralized decision-making in the hands of only a few officials.

While the US has successfully led a united Western front, with some Asian support as well, in pushing back against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the State Department has not been as effective in uniting the world against Iran or China.

Two veteran diplomats have also stepped down as special envoys for the Horn of Africa, lasting for less than a combined year.

On China, Gulf countries are looking to Beijing for economic and security pacts due to a perceived lack of US interest in the Middle East.

As for Iran, talks over reviving the 2015 nuclear deal appear to have been stalled – for now – over Tehran’s demands to have the terror designation lifted off the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC).

At least three members of the Iran negotiating team, which Robert Malley leads, have left in recent months.

In January, when it was revealed that Richard Nephew had decided to step down from his role as Malley’s deputy, the State Department sought to downplay any rifts and said personnel moves were “very common.”

But Nephew took to Twitter, saying he left on December 6 “due to a sincere difference of opinion concerning policy.”

Ariane Tabatabai, a senior advisor at the State Department, also quit her post on the Iran negotiating team. Her LinkedIn profile says that she started as a senior policy advisor at the Pentagon this month.

Sources familiar with her decision said Tabatabai decided to leave the team because Malley allowed Russia’s ambassador in Vienna to take the lead on the talks.

Tabatabai said she was “not doing any press at the moment” when contacted by Al Arabiya English.

Former US ambassador to Israel Dan Shapiro also left his role as a senior advisor to Malley after about seven months.

Malley and Nephew

Nephew said he left because he didn’t see eye to eye with the negotiating team’s policy. Shapiro said he initially joined for six months, something apparently agreed to beforehand.

But sources familiar with the negotiations have told Al Arabiya English that there was dissatisfaction among the negotiating team over Malley’s unwillingness to listen to opposing points of view.

Nephew reportedly briefed Senator Bob Menendez, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman and a critic of the JCPOA deal reached in 2015, and provided more information than Malley had agreed on.

Malley voiced his frustration to Blinken, said one source familiar with the discussions.

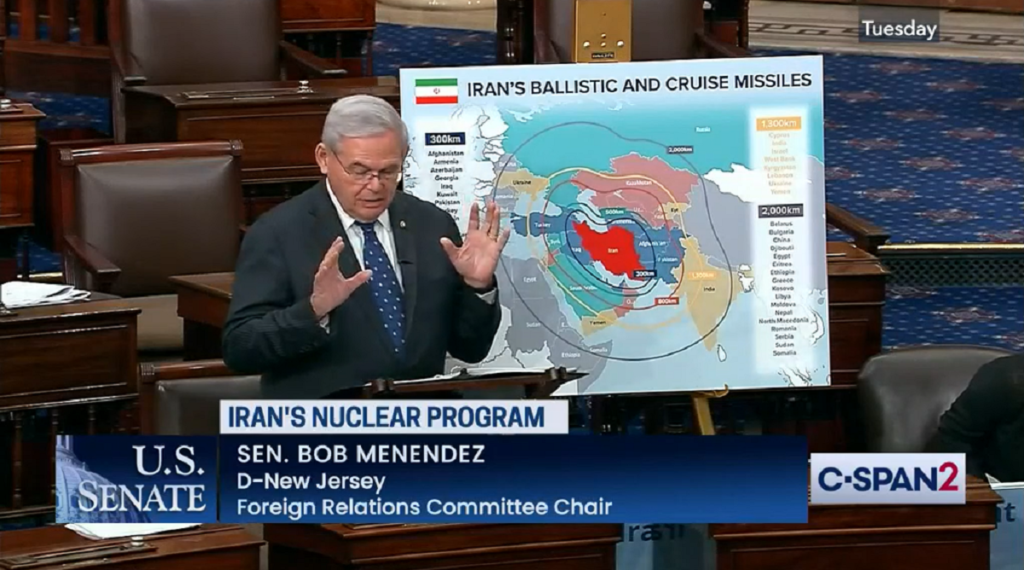

Days after news broke of Nephew’s decision, Menendez went to the Senate floor and blasted the 2015 nuclear deal during a 58-minute-long speech with billboards behind him of reasons why the deal was bad.

“As someone who has followed Iran’s nuclear ambition for the better part of three decades, I am here today to raise concerns about the current round of negotiations over the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action and Iran’s dangerously and rapidly escalating nuclear program that has put it on the brink of having enough material for a nuclear weapon,” Menendez said.

He added: “We cannot allow Iran to threaten us into a bad deal or an interim agreement that allows it to continue to build its nuclear capacity.”

Nephew “categorically” denied briefing US senators without Malley’s prior knowledge.

“Rob was fully aware of any legislative branch briefings I conducted and, in fact, directed me to undertake them as part of a robust effort to brief our congressional colleagues during my time on his team,” Nephew told Al Arabiya English.

Nephew said he was not making public comments about the Iran deal talks “out of respect for the fact that the negotiations are ongoing and any public comments that I might make could unfairly prejudice those talks or affect the US position.”

The State Department has said disagreements are normal. Al Arabiya English reached out to Menendez for comment but did not receive any response.

But in another sign that more American lawmakers and officials from both political parties are against the administration’s current attitude toward the indirect talks with Iran, which have been stalled for nearly seven weeks now, two motions were passed in the Senate on Wednesday.

One was proposed by Senator Ted Cruz and called for maintaining terrorism-related sanctions on Iran to limit China’s cooperation with Tehran.

Bipartisan support was evident after the motion was adopted 82-12.

Senator James Lankford put forth a motion that said any future deal with Iran should address its nuclear program, Tehran’s support for terrorism, and should not remove the terror designation from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

A number of prominent Democrats supported both of the non-binding motions, including Biden’s close aide, Senator Chris Coons and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer.

Disagreements evident in US-Africa policy

The US special envoy for the Horn of Africa was a role created by the Biden administration as it attempted to revitalize Washington’s sway in the area.

Violence and instability in Ethiopia and Sudan were the main focus, with shuttle diplomacy conducted between Washington, Khartoum, Addis Ababa and other African capitals.

Veteran diplomat Jeffrey Feltman was tapped to lead the diplomatic efforts, but he stepped down in January less than a year later.

Another seasoned diplomat David Satterfield was chosen to succeed Feltman. Like Feltman, he will be in that role for less than one year after saying he would resign before this summer.

Foreign Policy magazine reported that US diplomats were concerned about too much focus on Ethiopia and too little on Sudan.

Sources said that the Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Molly Phee’s moves to hold onto the decision-making and drive US policy in the Horn of Africa posed an obstacle to Feltman and Satterfield.

Foreign Policy also reported late last year about “clashes” between Feltman and Phee over sanctioning Sudanese officials and actors behind the coup, which ultimately led to the overthrow of Abdallah Hamdok.

Cameron Hudson, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center, recently wrote that Satterfield’s decision to step down was “consistent with the view that Horn envoys have been stymied by working through the lower-level assistant secretary for Africa.”

The State Department also played down rifts between US diplomats and Phee.

“For an administration that came in big on letting their career [diplomats] take the lead, you don’t see much interpretation of that in reality,” a Washington-based source close to current US officials and diplomats told Al Arabiya English, asking not to be named to speak freely on the matter.