Data shows siege and destruction of health system are causing preventable deaths in Tigray

Children are dying of malnutrition at increasing rates in Tigray due to a man-made humanitarian catastrophe, writes the head of Tigray’s health bureau.

Source: Ethiopia Insight

Since the war on Tigray began in November 2020, the Ethiopian military, its Amhara allies, and Eritrean troops have committed countless atrocities.

Most significantly, the war has resulted in the near-total collapse of the region’s health care system. Before the conflict, the region’s health system was based on a sturdy foundation with enhanced community engagement, in addition to an Early Warning, Alert, and Response System.

With the looting and destruction of facilities across Tigray, the family health system has collapsed. A damage assessment study conducted by Mekelle University revealed that 78 percent of health posts, 72 percent of health centers, and 80 percent of hospitals have been destroyed.

On account of the persistent denial of critical medical supplies, health facilities—including the regional flagship hospital, Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Referral Hospital—have run out of medication for chronic illnesses and other basic life-saving medicines.

Patients at Ayder have succumbed to otherwise non-life-threatening wounds because the hospital has run out of gauze. Post-surgery patients have died of septic shock due to the shortage of antibiotics.

The destruction has wiped out 20 years of progress, returning Tigray’s health system to a time when there were no decentralized essential health services.

Emergency conditions

One of the aspects of the siege imposed on Tigray is a communications blackout that has prevented the timely detection of emergency health conditions. Given this and the presence of numerous hard-to-reach areas, the extent of the crisis in Tigray is underreported.

While thousands in Tigray have already perished unnecessarily, many more are still perishing each week without the international community or even the regional government being aware of it.

In addition to the blackout, the fuel shortage has made it virtually impossible for health professionals to travel to remote areas and assess conditions. The federal government has denied the entry of fuel into Tigray since early July.

According to World Food Programme (WFP) estimates, the number of people in need of humanitarian support in Tigray has risen to 5.2 million, a figure that includes 3.9 million people in need of health assistance.

The WFP has said that 100 aid trucks are needed each day but only 1,355 have arrived since July. By severely limiting the number of convoys, the federal government has created a dire situation. It has produced an acute shortage of medical equipment, supplies, medicines, and vaccines, resulting in a large number of easily preventable deaths.

According to a report by the Tigray branch of the Ethiopian Pharmaceutical Supply Agency, all immunization antigens, health program medicines for TB/HIV and malaria, family planning supplies, and other essential health commodities have been out of stock for the past six months.

Rising malnutrition

The nutrition situation across Tigray has also been steadily getting worse.

The malnutrition rate among pregnant and lactating women is above 60 percent. Over 1.6 million children under-five and pregnant or lactating women need nutrition intervention.

Acute malnutrition in children under five has hit 29.1 percent, of which 7.1 percent have been diagnosed with severe acute malnutrition (SAM). This figure is well above the global emergency threshold of 2 percent, and 22 percent have been diagnosed with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM).

Across Tigray, 54 percent of water points are not functional, affecting water access to 3.5 million people. As a result of this humanitarian catastrophe, the famine classification is expected to reach the highest level, IPC 5, in the coming few months.

Mortality survey

A recent initial mortality assessment looked at priority health needs and associated intervention in terms of mortality for the first time since the outbreak of the war.

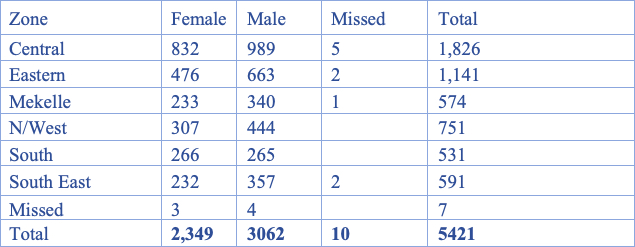

Data was collected from 333 tabias/sub-districts (40 percent of the total) of 53 districts in the Mekelle, Southern, Southeastern, Eastern, Central, and Northwestern Zones of Tigray.

The entire Western Zone is inaccessible since it is under occupation by Amhara forces and the Eritrean military. Parts of Northwestern, Eastern, and Southern Zones are also inaccessible for the same reason.

Since the magnitude of the destruction and health crisis in the inaccessible areas is undoubtedly high, the survey is bound to underreport the real extent of the crisis.

Data was collected by NGOs from their project sites in collaboration with the regional health bureau. Representatives of health facilities, wereda health and/or social affairs offices, and community/religious leaders were contacted using a template. The questionnaire asks for the deceased’s name, sex, age, area of residence, and cause of death, as clinically confirmed or as perceived by the respondent.

Death patterns

Out of 5,421 deceased recorded, 56.4 percent were male and 43.3 percent were female. The majority of deaths occurred in the age group 15 years and above.

Geographic variation of deaths by districts and zones is marked. Central and Eastern zones have a higher burden of deaths than other zones in the region due to the widespread and systematic destruction of the health system in these zones. Twenty-five districts (46 percent) face a large burden of deaths, accounting for 63 percent (3,098) of the deaths included in this report.

This depicts a pattern of war-related effects where some areas are more affected than others. The plundering and destruction of private properties and food stocks by the invading forces have led to severe impoverishment.

Place of death were recorded in the assessment for a total of 5,421 deaths. Of these, 77 percent occurred at home, and 20 percent at health facilities, with three percent not indicated. Compared to other areas, in Mekelle, access to health facilities is somewhat better and death at health facilities is relatively high. In the rest of the zones, death at home is higher than death at health facilities.

This suggests that the community could not use the health system as facilities were vandalized. In addition, due to the lack of critical medications, diagnostic tools, transport, and the unavailability of health service providers at health facilities, people in the region do not have access to basic health services.

Starvation deaths

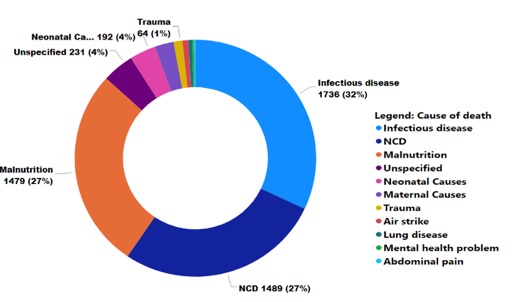

The causes of death data show that, since the onset of the war, Tigray has experienced a changing pattern of mortality. Deaths from infectious diseases (32 percent), non-communicable diseases (27.5 percent), and malnutrition or starvation (27.3 percent) have increased markedly. Under normal circumstances, such causes of death are easily preventable with sufficient food intake and proper medication.

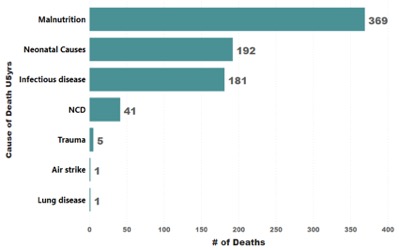

Causes of death in children under-five show that malnutrition is the leading cause of mortality followed by neonatal causes and infectious diseases.

This pattern can be attributed directly to the blockade, which has obstructed the delivery of humanitarian aid, diagnostic equipment, and life-saving medical supplies to the region. Predictably, medicine shortages were also reported by a large number of respondents.

In infants, neonatal causes account for over 51 percent of all deaths, followed by malnutrition (29 percent) and infectious diseases (17 percent). This can be explained by the fact that nearly 80 percent of all health facilities have been destroyed and so the increase in home deliveries out of necessity, along with the poor quality of obstetric and child health services.

Before the crisis, there were more than 43,000 HIV-positive patients and more than 100,000 cases of non-communicable diseases were under chronic follow-up. Mortality due to HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and other chronic conditions was very low. Nowadays, deaths from these causes have dramatically increased.

Intervention needed

In the absence of intervention by the international community, millions of Tigrayans will continue to face the risk of death due to hunger and lack of critical medical supplies.

Even where health care facilities were not seriously damaged, the extended siege of major towns and cities meant that medical supplies, as well as food, clothing, and fuel were prevented from getting through for long periods of time.

Healthcare personnel have not been exempted from the brutalities visited on the rest of Tigrayans, leading to a considerable loss of staff across Tigray.

An incalculable number of people have perished out of sight as the consequences of the siege, including the suspension of banking services, lack of fuel, and telecommunications blackout have made it nearly impossible to contact those living in remote areas of Tigray.

International response

This humanitarian catastrophe is going to worsen unless urgent measures are taken by the international community to break the siege and support the region to rescue its health system.

As thousands in Tigray perish due to hunger and easily preventable diseases, the international community continues to refer to “famine-like” conditions rather than explicitly calling out the man-made nature of the famine that is taking place in Tigray.

At a minimum, the international community must compel the Abiy government to allow unfettered humanitarian access to Tigray and stop its deliberate denial of critical medical supplies and other basic necessities, such as fuel, from getting into Tigray.

While the people of Tigray appreciate the expressions of concern, what they need are actions—actions that can make appreciable differences in the lives of the thousands of children condemned to death by malnutrition, with their bodies emaciated beyond recognition.

Feature image: A looted room at the Sebeya health center in the Eastern Zone of Tigray; March 2021; Médecins Sans Frontières.