Drone strikes in Tigray: a feminist reading

Source: Globe News Net

March 7, 2022

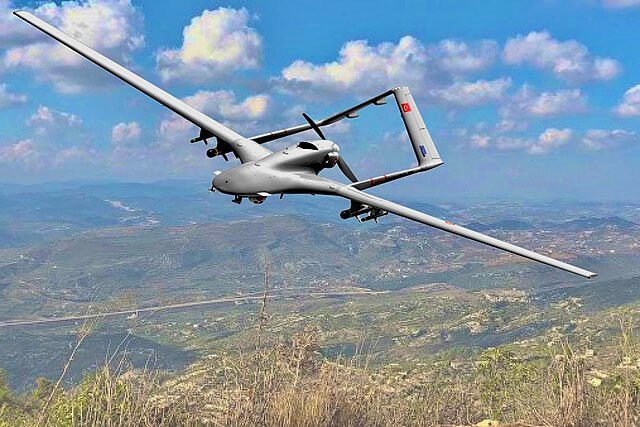

On March 7, 2022 the UN Conference on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) will convene the Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on lethal autonomous weapon systems to discuss the ethical issues raised by this new type of weapon and attempt to proactively advance the legislative framework. It may still sound like science fiction, but these systems are well on their way to commercialization. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVS) are a first step in the direction of autonomous systems. Initially presented as advanced systems reserved for the great powers, their production by medium powers has democratized their use.

The international community did not anticipate this diffusion, which led to a failure of the legal framework in their sale, circulation and finally their use by states. Ethiopia is a textbook case, and on several points we will return to it. In just a few months, “cheap” drones have demonstrated their effectiveness in Nagorno Karabakh, Yemen, and then Tigray, but in the latter case, it was the first time that a state has used them against its own population.

One of the reasons for UAVs’ success is technical: they are discreet, efficient and cheaper in cost and maintenance (including pilots) than fighter aircraft.

The list of commercial arguments is long. But this new weaponry induces a certain conception of war, based on dehumanization and impunity.

The enemies are made invisible, we no longer confront them, we no longer want to see them. This is perfectly suited to genocide, where the others are considered not only inferior, but so low that they are no longer part of the human family and must disappear. These devices are also stealthy, they have no neutralization weapon for the moment, and this is how strikes are carried out against civilians: without being seen, without being worried.

Organized starvation that kills without having to fight or even see the enemy is the other, ultimately quite similar, weapon used by the government of Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. Stepping back, this war clearly has no purpose. There is no conquest of territory or resources. The only object of this war is domination and as a corollary the subjugation of the Tigray (and other populations of Ethiopia, we too often forget).

According to Ray Acheson, Director of Reaching Critical Will and visiting researcher at Princeton University, domination and impunity are two central concepts that define the brutal masculinity at work in the use of lethal autonomous weapon systems. About American strikes, Lorraine Bayard de Volo, professor at the University of Colorado, notes that these operations emasculate the authorities of the territory in which they are carried out.

The one who carries out the strike is the self-proclaimed Patriarch who acts without the consent of the other, who finds himself in a position of powerlessness (since for the moment one cannot retaliate against drones) and in the incapacity to make the one who strikes accountable.

“Unmanned” Aerial Vehicle, the expression would be smiling if the reality it covers was not so dramatic. These machines are “manned” in their use, as a former drone operator of the Joint Strike Operating Command (JSOC) testifies when he confides that UAVs are nicknamed “Sky Rapers”. A feminist reading of the war in Tigray shows that the Ethiopian government acted as a “brutal male” seeking only domination, and it is no coincidence that sexual and gender-based violence (SGBVs) were used systematically and orderly by the government’s allied troops.

The central government wanted to make it technically impossible for the Tigray government and the Tigrayan armed forces to protect civilians, “their civilians“ if one is to follow the rhetoric of ownership and protection of the weak by the alpha male. Independently, Dyan Mazurana, experienced researcher and specialist in gender studies, comes to a similar conclusion about weaponized rapes: “it is important to understand that much of the violence is about males communicating with other males, as well as women and girls, about their masculinity, as well as the presence or lack of other males’ masculine abilities. While maleness is a biological construction, masculinity is a status that must be affirmed by oneself and others. In this way, male perpetrators use violence to demonstrate their power over Tigrayan women and girls, as well as over their victims’ fathers, brothers and husbands and, symbolically, over the larger Tigrayan ethnic community.”

The defenders of patriarchal and centralizing authoritarianism will quickly label other models, such as federal, participatory and inclusive, as weak or even effeminate, but they are driving the nail into the coffin of gendered constructions. This vision has lived on and demonstrates every day its vacuity and the dead end it leads to. The Tigrayans, who promote federalism and include large numbers of women in their armed forces, are standing up to one of the strongest armies on the continent.

Changing representations is not within the power of legislators, but preventing impunity is. At a time when we think about the ethical issues raised by killer robots, the use of UAVs against civilians must be regulated and accountability against perpetrators of SGBV must be guaranteed.

Tomorrow, Tuesday March 8, will be International Women’s Day. Among other things, this day serves to highlight concrete initiatives to improve the situation of women and children around the world. At the intellectual and symbolic level, a feminist or gender vision of the world is not a reversal of the magnetic poles. It is about rethinking living together in a non-competitive way.

This is perhaps utopian, but no one, in all honesty, disarmed of any social, ideological or religious bias, will deny that such a vision is seductive. Amid the Ukrainian crisis, where once again the imperialism of the dominating male is showing the full extent of its power to harm, it is becoming imperative,