Source: Reclaim Eritrea

September 25, 2021

Armed conflict between the Ethiopian military and forces loyal to the ruling Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) erupted in November of 2020. The confrontation between these two forces is the culmination of long simmering tensions that presaged what many warned could lead to the outbreak of a full-scale civil war. Eritrea’s dictator, President Isaias Afwerki, a leader whose own government has waited decades for an opportunity to settle old scores with the TPLF, has committed the full force of his nation’s military to bolster Abiy Ahmed’s military campaign.

Eritrean troops have poured into Tigray in great numbers and their ranks have seemingly been given carte blanche to let loose an avalanche of terror on the civilian population. The rapaciousness with which Afwerki’s armies have prosecuted his bloody intervention in Tigray stands in stark contrast with the hopes for peace that followed a July 2018 agreement signed between Afwerki and Ahmed, formally ending a two-decade border conflict between Eritrea and the then TPLF-led Ethiopia.

What was then perceived by many Eritreans as the inauguration of a new political dispensation gradually proved to be illusory; war and devastation would soon follow. The repercussions of Afwerki’s actions in Tigray can generally be broken down into three categories of failure: 1) national security, 2) economic, and 3) moral. It is to these actions and their consequences that I now turn.

National Security: Why the war in Tigray has made Eritrea less safe.

Since the fateful decision to fully cooperate in Ahmed’s invasion of Tigray, Afwerki’s regime has insisted on the right to eliminate the TPLF as an existential threat to the state. National security, therefore, has underpinned every justification to continue Eritrea’s military involvement in Tigray. Initial calls for restraint were met with facile refrains that the fighting was not a war but an internal “law enforcement operation” that would “wrap up soon.”

However, nearly a year after the conflict began, the TPLF has launched a series of lightning offensives that have succeeded in recapturing most of their territory, including the regional capital of Mekele. Their string of military victories have been aided by the growing number among their ranks, swelled in no part due to the counter-productive strategy of rape and murder employed by Afwerki.

However, what is of greater concern is not only the failure to destroy the TPLF or capture any of its leadership, Afwerki has also failed in preventing the group from creating alliances with other insurgents such as the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) and widening its offensive beyond Tigray’s borders. This dangerous development has led to scores of civilians being killed in neighboring Amhara and Afar regions, which in turn has incited a military mobilization in each regional state, and created the real possibility that Ethiopia could descend into an ethnic civil war.

Afwerki’s invasion has therefore not only exacerbated the crisis and created the real risk of state collapse in one of Africa’s most populous states, it also leaves Eritrea itself vulnerable to attack on its own territory. I believe that the chances for state collapse are real in Ethiopia. And if the center does indeed fall, the conflict and concomitant refugee outflows that will inevitably result will destabilize and engulf Eritrea.

Even if one were to consider a reality in which Afwerki and Ahmed’s war of annihilation succeeded in liquidating the TPLF completely, Eritrea will have created a larger threat to its security: the people of Tigray themselves. Future generations will not quickly forget the terror met on their forebears.

This resentment has the potential of manifesting itself in the form of a resurgent Tigrayan nationalism and could perpetuate a cycle of violence between the two peoples that could persist for generations. Thus even when considered in the light most favorable to Afwerki, a military triumph over the TPLF at this juncture promises to be hollow.

Self-Imposed Economic Sabotage

The rise of Ahmed and side-lining from power of the TPLF in 2018 provided Afwerki with an opportunity to reset economic relations with Ethiopia and to liberalize the Eritrean economy. Indeed the TPLF and its intransigence on the border issue was constantly blamed as the source of Eritrea’s economic woes. Soon after the peace accord, Eritrea opened its borders with Ethiopia and the benefits were immediate. Road and air links were re-established and phone lines were restored. This not only reacquainted the two peoples to one another after a prolonged interlude, it also reunited families who had not seen or communicated with one another in decades.

The Eritrean people profited mightily from the re-opening. Long handicapped by Afwerki’s economic restrictive policies, goods from Ethiopia’s vast interior flooded the Eritrean market, dramatically reducing the prices of foodstuffs such as teff (wheat) and building materials like cement and construction cables. Much of the trade that flourished during this period occurred between the people of Eritrea and neighboring Tigray, whose close proximity to one another’s markets often made it easier for merchants and customers to access goods that were too inconvenient and costly to access in their own countries. Renewed cross border movement also allowed tourism from Ethiopia into Eritrean towns such as Asmara and Massawa, producing a mini-boom.

This flourishing of economic activity was abruptly cut short by Afwerki less than one year after the peace accord when he unilaterally closed all border crossings with Ethiopia. No explanation was ever given for this action but what followed was a reversal of the economic benefits brought about by the reopening of borders. This arbitrary decision angered many Eritreans who, for the first time in 20 years, had begun to see their economic conditions improve. Domestic and foreign investment interest, initially ascendant, soon flat-lined.

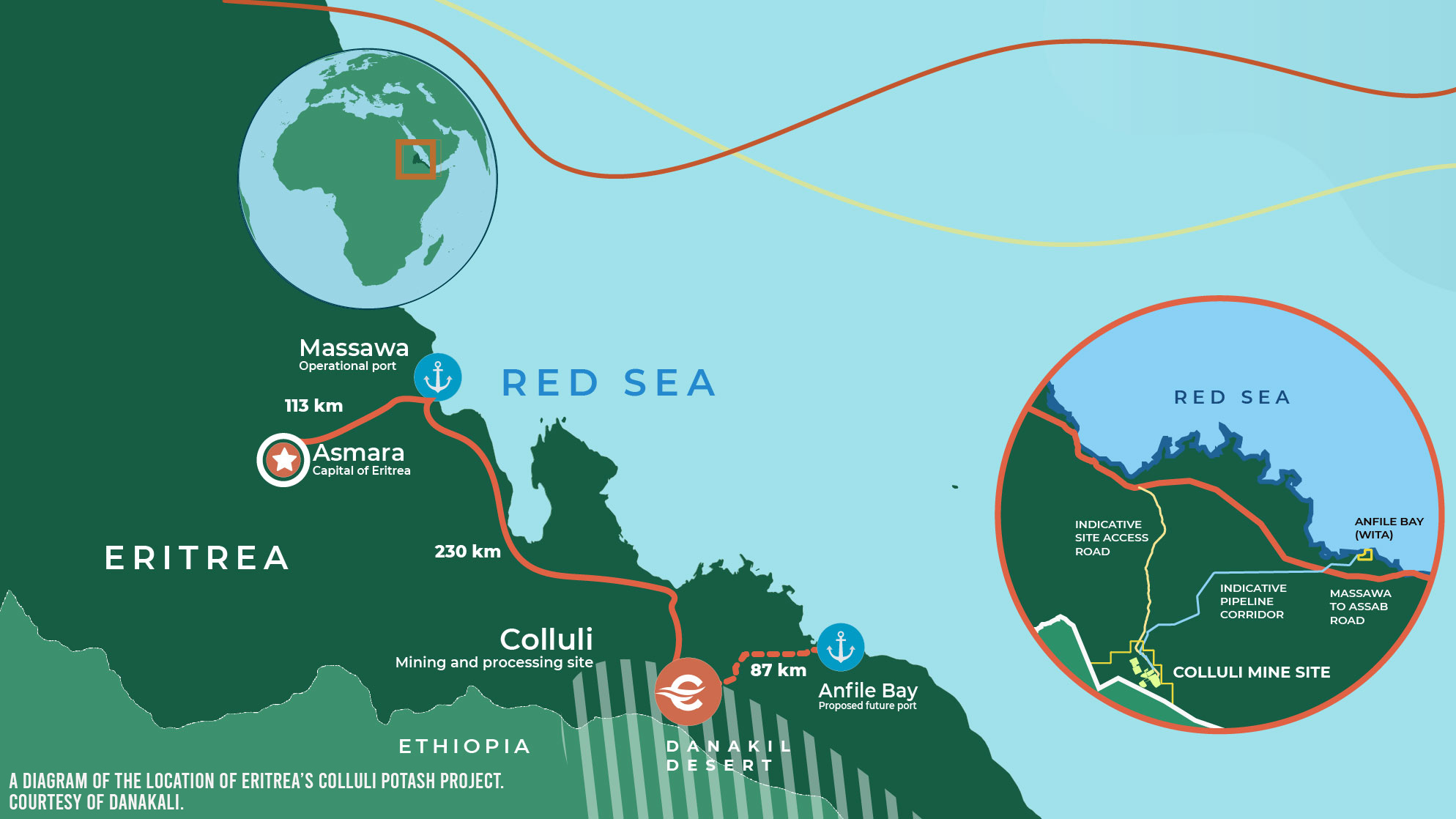

Of particular note is the shared interest both nations have in the extraction of potash, a high-grade fertilizer located in huge deposits beneath the border that straddles the Afar regions of both nations. This mineral has been called a “game changer” for Eritrea’s economy. Ethiopia, which has considerable deposits of its own, stands to also gain from the export of this natural resource. The presence of these untapped potash reserves also has the potential of alleviating the high cost both countries pay to import fertilizer for their agricultural sectors.

Initial plans included the construction of a new Eritrean port to export potash from both Eritrean and Ethiopian mines to international markets. However, Afwerki’s border closures halted these plans and indefinitely froze the promising developments that were underway in this emerging sector of the economy.

Moreover, his subsequent decision to join the war in Tigray has exacerbated the fragile security situation in the Afar regions where these huge mineral deposits are located. Inhabitants on both sides of the border harbor grievances against their respective central governments and accuse them of exploitation. In the past, this animosity has manifested itself in open acts of sabotage and violence against foreigners and mining interests.

The inability to prevent the TPLF from spreading the conflict into this resource–rich land and potentially destabilizing it even further represents a major strategic failure on the part of Afwerki and his allies. When considered in the context of Eritrea’s 30-year economic malaise it also serves as a microcosm for the lack of foresight and incompetence that has characterized Afwerki’s rule.

Moral Crisis: What’s been Done in Our Name

Oxford defines a total war as “a war which is unrestricted in terms of the weapons used, the territory or combatants involved, or the objectives pursued, especially one in which the accepted rules of war are disregarded.” Perhaps the most horrifying manifestation of this type of war occurred during World War II, when the armies of the Third Reich launched Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union.

The devotion and scale with which Hitler’s armies exterminated entire populations as they invaded and engaged in a deliberate campaign of terror in the conquered territories knows no parallel in the annals of modern warfare. It shocks the conscience of this writer to witness Eritrean troops become party to a similar campaign, albeit on a smaller scale, in Tigray.

Multiple international organizations such as Amnesty International (AI), Human Rights Watch (HRW), and the United Nations (UN) have reported mass killings, rapes, and indiscriminate mass looting. These reports strongly implicate the Eritrean army in war crimes. Similar accusations have been lodged against Ethiopian forces. Ahmed, to his credit, has had the political tact to publicly respond to these accusations by committing to investigate those responsible for crimes. In May, his government went so far as to point the finger at Eritrea for the infamous Axum massacre.

Neither Afwerki nor any of his inner circle has issued a formal statement regarding these serious charges, or indicated an interest in investigating the conduct of the Eritrean army. Such silence has a sound, the sound of the criminal. The Eritrean people are therefore confronted with a moral crisis that most of them did not help create but one which they will be saddled with long after the guns fall silent in Tigray. Among many of history’s cruel ironies is the frequency with which the victims of terror become the purveyors of that same terror. Sadly, Eritrea has not escaped this tragic pattern.

Eritrea’s military in particular bears a unique guilt. It evolved from the Eritrean People’s Liberation Army (EPLA), a guerrilla army whose membership grew exponentially during the liberation war against Ethiopia due to the same types of atrocities now being brought upon the people of Tigray.

During that war the EPLA developed an international reputation for the humane treatment of civilians and, although it was not a signatory to any international convention related to their treatment, they still pursued a policy of returning POWs through the auspices of the International Commission of the Red Cross (ICRC).

This legacy would become one of the moral wellsprings of the nascent Eritrean army and a source of pride for the Eritrean people. It’s unfortunate that such a rich heritage has become a casualty of the current conflict.

Conclusion

Amidst the cruelty and collision of physical forces lies the crude accounting all peoples make when a leader commits the nation to war. Under any measure of success, Afwerki’s intervention in Tigray has failed to subdue the TPLF and extricate Eritrea from the economic and security quagmire his policies have placed the country in.

On the contrary, it appears his actions have exacerbated these underlying problems and shut the small window of opportunity there was for peace that appeared in 2018. The war continues unabated, and it has reached a level of such merciless brutality that I do not believe a negotiated settlement is possible between the parties. It has indeed become a war of annihilation.

For Eritreans, therefore, Afwerki’s gambit has risked the very stability of the state they fought so hard to create.