Source: Ethiopia Insight

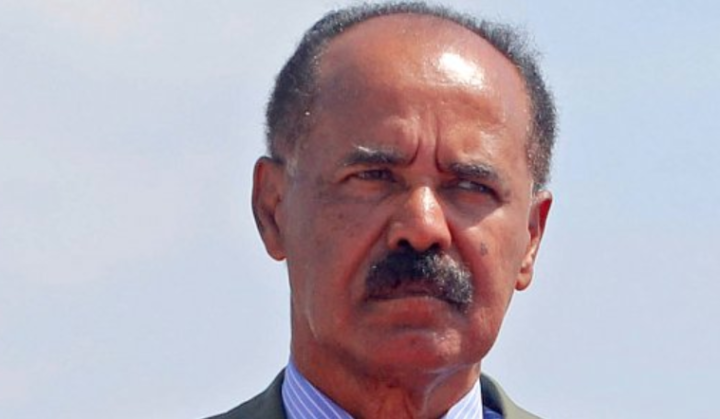

In an interview with the Eritrean state-owned television network on 8 January, President Isaias Afwerki critiqued the Ethiopian constitution by saying it was designed to institutionalize ethnic identity, and that the federal system it prescribed is the source of all problems in Ethiopia.

These opinions are not new. In many of his interviews, Isaias has passionately reiterated that Ethiopia should engage in a centralized nation-building project and abandon ethnic federalism.

However, he is not saying this out of concern for the welfare of Ethiopia. Rather, the reason for his obsession with this topic is that Eritrean nation-building is hampered by the presence of a Tigrayan identity that transcends the current state boundaries.

Nation-building

All of the countries in the Horn of Africa were created during European colonialism in the 19th century and have cross-boundary ethnic groups. For instance, Oromos live in Ethiopia and Kenya; Afar in Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Djibouti; Somalis in Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Somalia; and Nuer in Ethiopia and South Sudan.

Similarly, Tigrayan people live in Ethiopia’s Tigray region as well as in Eritrea. In the late 19th century, Tigrinya speakers were divided and incorporated into the Italian colony of Eritrea and the Shewan-led kingdom of Ethiopia. They are an overwhelming majority in Eritrea, mainly occupying the country’s highland areas.

Isaias has been trying to construct a singular, Eritrean national identity from the nine ethnic groups in Eritrea. His nation-building project thus requires that the identity of the Tigrinya-speaking people of Eritrea be eliminated and that a new, Eritrean identity is cultivated.

However, the Tigray nation is relatively homogenous, with no clan structures and with deep social trust. The people on both sides of the border share the same language, religion, history, and territory.

Even many of the current leaders of the ruling People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) party, including Isaias, are either from Tigray or have parents from Tigray.

Conversely, many top Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) leaders, including the late Meles Zenawi, have parents from present-day Eritrea.

It is thus almost impossible to separate the Tigray nation into Eritrean and Ethiopian camps. Accordingly, Isaias is of the opinion that his nation-building project can’t easily be finalized without Ethiopia adopting the same approach.

Assimilationist need

Isaias has long understood that without Tigray’s complete assimilation into Ethiopia, Tigrayans in Eritrea would not give up their identity, and this would stymie the project of constructing a common Eritrean identity.

Accordingly, for his project to be successful, the Ethiopian federal arrangement that protects and promotes group identities should be abolished and the assimilationist nation-building project needs to be revitalized.

Once Tigray is sufficiently assimilated into Ethiopia, his hope is that the national consciousness of Tigrinya speakers in Eritrea will weaken, which will help in realizing his project.

This demonstrates that the core reason for the rivalry between Isaias and the TPLF was the fact that the latter defended ethnic federalism.

TPLF accommodation

TPLF’s original objective was to establish Tigray as an independent nation-state. But, these ambitions evolved over time.

The Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) was by far the most powerful rebel group fighting the Derg regime. TPLF thus sought support from EPLF and compromised its original objective of securing Tigray’s independence.

According to Isaias, the alliance made TPLF shift its goals. TPLF half-heartedly changed its program from establishing a republic of Tigray into staying in a federated Ethiopia.

Isaias’ expectation during the immediate post-Derg era was that TPLF would rule Ethiopia as a unitary state, or at least not as an ethnic federation.

But, to his displeasure, the 1995 constitution not only adopted a multi-national federal system but even gave the nations, nationalities, and peoples of Ethiopia a self-determination right that included a constitutional right to secede.

In an interview, he said, “Not just Article 39, but the whole spirit [of the constitution] is not one that you would crave for nation-building….In my reading, it is not good for the people of Ethiopia or any other people.”

Eritrean meddling

Isaias also thinks that Eritrea is justified in meddling in Ethiopia’s affairs for national security reasons.

In the same interview, he said, “We can’t say [Ethiopia’s domestic] affairs are their own. What we saw during the past sixty or eighty years over three generations is that [our affairs] are directly related to the situation in Ethiopia. We can live in peace, brotherhood, collaboration, and respect [with Ethiopians]. But, first, the stability of Ethiopia needs to be determined.”

He also revealed his disappointment with the Ethiopian government pulling out its armed forces from most of Tigray last June, while also implying that Eritrea could continue its military intervention in Ethiopia with greater intensity.

Autonomy struggle

Although Isaias accuses TPLF of introducing a toxic and divisive system by institutionalizing multinationalism and self-determination, TPLF was partly dethroned in 2018 because it violated the constitution and installed a de facto centralized party-state system that undermined groups’ self-determination rights.

The main reason behind historic strife in Ethiopia has been the question of self-determination, as ethnic groups struggled to achieve self-governance and socio-economic justice.

Since Ethiopia’s formation as a modern state, there have been recurrent conflicts between two camps: those who have wanted to dominate and assimilate others, and those who have resisted that and struggled for independence.

Nationality and self-determination questions have been at the heart of every war and rebellion since Ethiopia’s expansion in the late 19th century. The social forces behind the movements that removed the imperial, military, and TPLF-led regimes centered on such questions.

At the heart of the Qeerroo movement that helped bring down the EPRDF, for instance, were the historical and modern-day cultural suppression, economic exploitation, and political oppression of the Oromo that included the denial of genuine self-administration.

Failed unity

A nation-building project via centralization has repeatedly failed in Ethiopia.

The imperial era centralization project failed when the Derg took power in 1974. The Derg continued the project through massive militarization and villagization programs. But this, too, had proven to be a failure by 1991.

The EPRDF’s policies of a centrally managed, highly monopolized economy that trumped regional states’ autonomy proved to be a continuation of the same centralization project.

Abiy’s similar attempts have led to the current crisis and the failure of the much-anticipated democratization process.

What Ethiopia now needs is a radical devolution where power is given to regional states and lower constituent units. Accordingly, nation-building of the type President Isaias demands is practically impossible in Ethiopia. His prescriptions for Ethiopia are destructive, and, if implemented, the backlash could lead to the federation’s complete disintegration.

Exporting disaster

Although its present-day borders were created by Italian colonialism, Eritrea was one of the oldest and most powerful civilizations in the world during the Aksumite Empire.

It was the cradle of the Ge’ez civilization and the Axumite trading empire across the Red Sea, while Adulis was the trading hub for global merchants.

Despite being an independent Italian colony, Eritrea was denied sovereignty by the United Nations after World War II. At the time, it was in the interest of the US and allied powers that Eritrea was yoked in the name of federation with Ethiopia. The invasions and encroachments made Eritrea’s history full of agony and resilience.

Finally, Eritrea secured independence in 1993 and restored its dignity.

Even after going through a destructive war of independence from Ethiopia between 1961 and 1991, Eritrea had a solid potential for industrialization, in part due to the infrastructure built by the Italians.

Yet, thanks to Isaias’ authoritarianism and nation-building effort that he embarked on a few years after independence, Eritrea has been experiencing a post-independence stagnation. His brutal nation-building scheme has isolated the country from the international community and put its potential to waste. His disastrous policies have created an all-around socio-economic debacle.

Furthermore, he imposed his totalitarian vision via the inhuman national service program. He underdeveloped Eritrea, seemingly intentionally, and is now trying to export his disastrous policy to Ethiopia.

Sadly, some Ethiopian politicians want to do what Isaias has done and engage in a unitarist, assimilationist program.

But, Eritrea can’t be a role model for diverse Ethiopia, as Eritrea is a de facto nation-state with an overwhelming majority of Tigrinya speakers.

Isaias’ brutal and repressive tactics such as forced conscription have led to an exodus of Eritrean youth, which then, paradoxically, created internal stability. This gives Isaias the upper hand over Eritrea’s unstable neighbors.

Unholy trinity

There are three powers that strive to dominate the Ethiopian center and impose their preferred systems: Isaias, TPLF, and unitarist Ethiopian forces. This trinity poses a threat to the self-determination rights of the nations, nationalities, and peoples of Ethiopia.

Therefore, a balance of power should be put in place to prevent the hegemonic ambitions of Isaias or any one of these three political forces.

The force that can defeat Isaias’ ambition is Tigrayan nationalism. Freedom fighter veterans who served during the armed struggle for independence under the EPLF are now forging such a movement. They are also mobilizing the youth in the diaspora. This movement is already delegitimizing Isaias in the diaspora.

Even the internal political dynamics of Tigray are being shaped by the explosion of Tigrayan nationalism that is challenging any hegemonic ambition that TPLF might have.

Abiy’s government should distance itself from Isaias and mend its relations with the international community. It should also build consensus with federalist political elites within the country, mainly those in Oromia, as this would help in curbing the assimilationist ambitions of the unitarist camp.