Kenya’s UN Ambassador went viral for chastising Moscow’s Ukraine invasion, but the principles of international law are crumbling on his own continent too.

Source: Responsible Statecraft

March 4, 2022

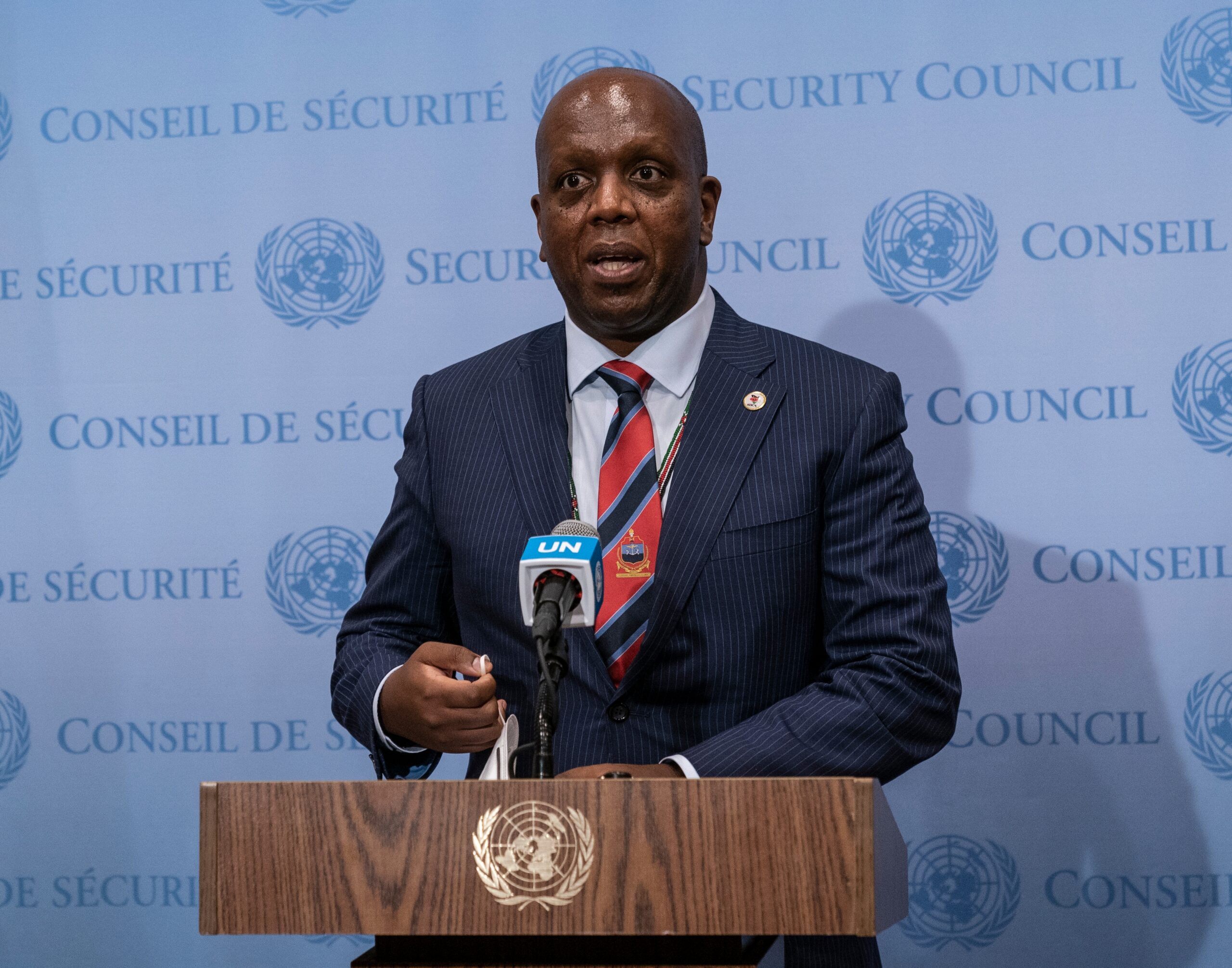

For a Kenyan diplomat, the flames of war in Ukraine resonate with his experience closer to home. Martin Kimani, representing Kenya at the United Nations Security Council, spoke about the flaring of “the embers of dead empires.” He condemned Russia’s actions and made a passionate appeal to uphold the principles of multilateralism.

While Europe, reeling under the shock of Russian aggression, is rediscovering liberal multilateralism, Africa is trampling on its own peace and security architecture, built by painstaking work over 25 years — a double standard graphically depicted by the Kenyan cartoonist Victor Ndula. At the African Union summit last month, the continental organization lived down to the old jibe that it was no more than a trade union of despots.

Kimani’s February 22 remarks, picked up by news outlets around the world, made the case that the multilateral world order, among other principles, is being challenged by Russia in Ukraine. At independence, he noted, Africa inherited arbitrary borders drawn by colonial powers. Rather than seeking to redraw them in pursuit of ethnically homogenous countries, which would have condemned Africa to “still be waging bloody wars these many decades later,” he said, the continent chose to “follow the rules of the Organization of African Unity and the United Nations Charter, not because our borders satisfied us, but because we wanted something greater, forged in peace.”

Without naming names, Kimani also called out other “powerful states, including members of this Security Council, [for] breaching international law with little regard.” It was a telling commentary from a nation three of whose neighbors are beset by violent conflict — Ethiopia, Somalia, and South Sudan.

Social media users in the Middle East have been quick to accuse the Western media of double standards in their coverage of the Ukraine crisis compared to their depiction of Afghanistan and Syria. There’s also ample evidence for racism in the treatment of non-Europeans trying to flee the war. But in Africa, the double standards start at home.

Since Emperor Haile Selassie addressed the League of Nations in 1936, when his country was invaded by Mussolini, African leaders have championed multilateralism. The continent’s multilateralism has the unique feature in that it grew from people’s resistance movements and not from a concert of powerful states. Nonetheless when the OAU was established in 1963, with its headquarters in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, it adopted a conservative doctrine of national sovereignty. The reason was to protect the fragile independence of newly decolonized countries, fearing that former European masters and white minority regimes would play their familiar divide-and-rule games. It was in this context that African states accepted the inviolability of inherited boundaries.

Over time, however, the OAU’s insistence that its member states should be entitled to conduct their internal affairs as they wished provided cover for despotic repression. By 1990, with pressures for democracy rising and South Africa, the last bastion of white minority rule, preparing to surrender to majority rule, the OAU needed reform.

Intense debates resulted in the creation of the African Union in 2002 — with more ambitious norms, principles, and institutions. Its Constitutive Act commits African states to cooperation in pursuit of peace, democracy, and human rights. It includes the doctrine of “non-indifference” to mass atrocities — Africa’s precursor to the United Nations’ “responsibility to protect” — fashioned in the wake of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

The AU creatively adapted its principles to support democratic uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt in 2011 — but faced a crisis with the Libyan civil war. The African Union and Russia criticized NATO’s intervention in Libya for disguising regime change under the “responsibility to protect.” They jointly pressed for a negotiated transition, which was dismissed by NATO in humiliating fashion — dividing and damaging the AU as well as fueling Moscow’s enduring distrust.

Today’s African leaders are turning the clock back. A spate of coups in West Africa recalls the dark days of the 1970s. While much of the rot is internal, there’s also a link here to Russia, which has been expanding its influence in the continent, offering weaponry and military services in return for access to minerals and votes at the UN. The Malian putschist Colonel Assimi Goïta turned to Russia’s Wagner Group and its paramilitaries in preference to French troops, and January’s coup makers in Burkina Faso encouraged pro-Russian rallies.

Last October, Sudan’s generals seized power, reversing the country’s democratic gains following the ouster of President Omar al-Bashir in 2019. The junta’s number two, Mohamed “Hemedti” Dagolo, was in Moscow just last week. Hemedti commands the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, drawn from the notorious Darfurian Janjaweed Arab militia, which has become a transnational mercenary enterprise linked to the Wagner Group, marketing its “anti-terrorism” services with glossy commercials.

Despite these glaring setbacks, the AU’s summit last month limited itself to pro forma reprimands of military rulers who are violating its foundational principles.

The Eritrean president, Isaias Afewerki, has ruled his country for 31 years without a constitution, rule of law, or parliament and has attacked each of his neighbors. Eritrea is the continent’s largest per capita generator of refugees, as young people flee indefinite forced conscription. Yet Isaias attended the AU summit and was welcomed by delegates who lauded his contribution to peace and security.

Kimani’s remarks about the embers of empire had a special resonance in Ethiopia, which was itself an imperial state, in which kings from the northern highlands conquered other peoples and forcibly incorporated them as their subjects. Thirty years ago, a new federal constitution sought to lay that history to rest, recognizing collective rights to the country’s numerous “nations, nationalities and peoples.” But nostalgia for imperial glory lived on, and, after coming to power in 2018, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed rekindled those flames, with a mystical, religious vision of Ethiopia. Such passions have led Ethiopia into wars of contending ethno-nationalisms, fought in coalition with Eritrea under the terms of a still-secret treaty.

In the war’s early weeks, Ethiopia rebuffed a South African-initiated offer of mediation. Abiy insisted the action was a legitimate “law enforcement operation.” It took six months of bloodshed before he conceded it was indeed a “war” and reluctantly accepted an African Union “high representative” — flirting with, but not yet accepting peace talks. Since last summer, Abiy has imposed a starvation siege on Tigray, which does not appear on our television screens because no journalist is permitted to go there. The AU has not uttered a word of protest.

AU headquarters is in Addis Ababa, but protocol dictates that when a summit is held there — as it was last month — the host is the AU Commission itself, not Ethiopia. In breach of that principle, the AU invited Abiy to welcome Africa’s heads of state. The thematic focus of the summit was launching Africa’s “year of nutrition.” Abiy and every speaker spoke about the importance of food; none mentioned the starvation crimes perpetrated by their host, even in passing. The AU’s own principles were tossed aside in a show of smug solidarity.

Across Africa, democracy activists are impressed by the speed, scale, and vigor of the American and European response to Russia’s attack on Ukraine. If Western nations held these principles and had these instruments to use, they ask, why did they fail to do so in the cases of Mali, Sudan, and Ethiopia? It’s a fair point. But the first responsibility for upholding such principles and using available instruments falls on the AU.

Despite Kimani’s stirring words, Africa is turning its back on the principles of international law so cherished by the founding fathers of independence and the leaders of its renaissance at the turn of the millennium. Twenty-five of the 47 countries that abstained or didn’t cast a vote on the UN General Assembly resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine this week were African. Eritrea was one of the four that joined Russia in voting against. Along with last month’s AU summit, Wednesday’s tally of votes is a sad record of Africa’s rapid retreat from a norm-based international order.