Dozens of Civilians Killed, Injured in Northernwestern Tigray

Source: HRW

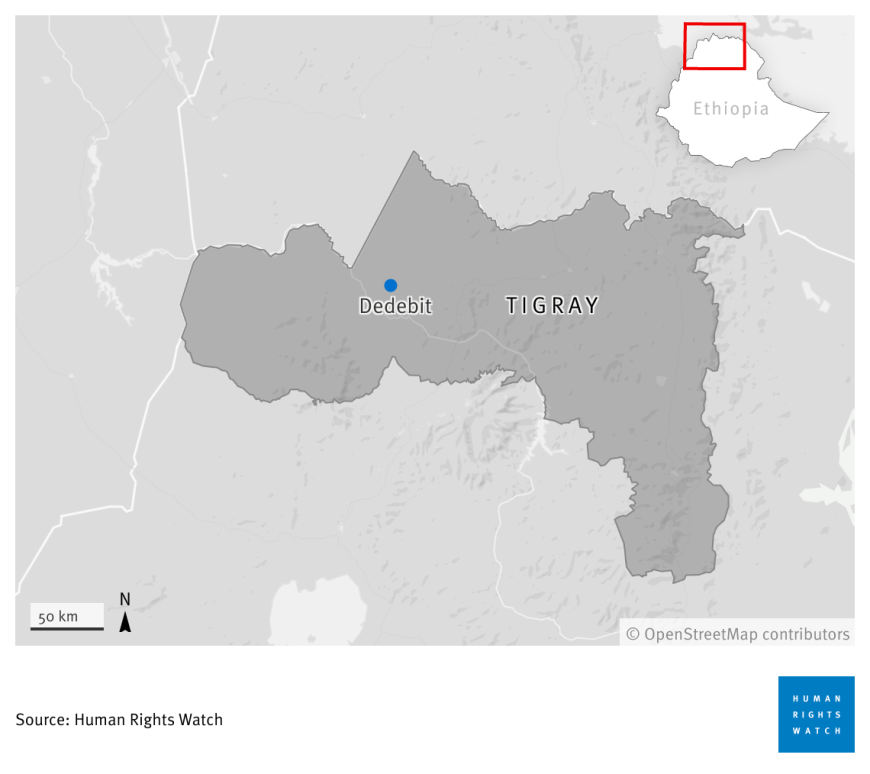

An Ethiopian government airstrike hit a school compound hosting thousands of displaced Tigrayans in northwestern Tigray on January 7, 2022, Human Rights Watch said today. An apparent armed drone dropped three bombs on the compound in the town of Dedebit, killing at least 57 civilians and wounding more than 42 others.

The Ethiopian government should carry out a prompt, thorough, and impartial investigation of the apparent war crime and appropriately prosecute those responsible. Because of widespread abuses by all sides to the conflict in northern Ethiopia, foreign governments should impose a moratorium on arms sales and military assistance to the warring parties.

“The Ethiopian drone struck the Dedebit school compound three times, killing and maiming displaced Tigrayans, mainly older people, women, and children, as they slept in plastic-sheeted tents and a school building,” said Laetitia Bader, Horn of Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Using guided bombs without evidence of any military target indicates that this was an apparent war crime.”

Since November 2020, Ethiopian federal forces and their allies, including Eritrean forces, have fought an armed conflict against Tigrayan forces affiliated with the region’s former ruling party, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). Government airstrikes in Tigray rose in October 2021 and increased significantly in mid-December following the withdrawal of Tigrayan forces from the neighboring Amhara and Afar regions. The Ethiopian federal government is the only party to the conflict that has acknowledged possessing drones, and at whose airbases armed drones have been reported in the media and seen on satellite imagery.

Airstrikes harming civilians have continued into 2022. The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights reported that between November 22 and February 28, her office had documented that 304 people died and 373 were injured from aerial attacks in Tigray – including two strikes in the town of Alamata in December and a strike in January that hit the Mai-Aini refugee camp hosting Eritrean refugees – and to a lesser extent in the Afar region.

Human Rights Watch interviewed a survivor of the Dedebit attack; two relatives of three victims; three aid workers, one a doctor, who visited the Dedebit elementary school prior to and after the strike; and a medical official who treated those injured in the town of Shire, 70 kilometers away. Human Rights Watch also verified 38 photos and 6 videos showing strike victims and debris, and reviewed satellite imagery collected before and after the attack.

On the night of January 7, three munitions detonated inside the Dedebit elementary school compound, hitting one school building and two spots near the barbed wire fencing where tents for displaced people had been set up in early January.

“It was the night of [Ethiopian Orthodox] Christmas,” a 70-year-old survivor said. “When the first strike happened, I was asleep with my family, I felt like fire hit us. I stood up, not knowing what was happening. Before I realized what was happening, the second strike happened, and then the third. At first, I thought fighting had broken out in the camp. But then I could see bodies were scattered, heads separated from one another. I realized this wasn’t fighting.”

An aid worker who visited the compound the next day said, “It was impossible to say how many were killed. They were burned to ash…. The ash was in the school compound. There are trees in the surrounding area where cut [dismembered] bodies were found. The damage was inside the compound, damaging three rooms of the school.”

Human Rights Watch obtained a list compiled by the displaced community with the names of 53 people killed immediately, including 32 females and 21 males. Fifteen of those killed were children, the youngest a year old, and 18 were over 50. The list stated that all the victims had been displaced from the town of Humera in Western Tigray, where Amhara forces controlling the town had expelled Tigrayan women and young children, as well as sick and older people, in November and December.

Doctors at a hospital in Shire described treating at least 46 people with abdominal trauma, destroyed limbs, and other injuries. Of the 46, one child was dead upon arrival and three others died at the hospital. One doctor noted that the hospital lacked basic medical supplies, such as surgical gloves. Since late June 2021, the Ethiopian government has imposed an effective siege on Tigray. Medical supplies were blocked from entering the region until mid-January.

Satellite imagery and photos Human Rights Watch analyzed show significant destruction to one of the school buildings as well as at two spots in the compound where temporary shelters and structures for displaced people had been set up.

Displaced people and aid workers collected remnants of the airdropped munitions at the site, including distinctive guidance fins and body fixtures that allowed Human Rights Watch and others to make a positive identification of the weapon used as a MAM-L “smart micro munition” delivered by Bayraktar TB-2 drones as well as other light aircraft. Human Rights Watch concluded that a variant of the MAM-L guided bomb with an “enhanced blast” warhead was most likely used because of the wounds and level of damage. Enhanced blast weapons are more powerful than conventional high-explosive munitions of comparable size and inflict extensive damage over a wide area and thus are prone to indiscriminate use when used in populated areas, Human Rights Watch said.

Human Rights Watch found no evidence of military targets at the Dedebit displacement site. The survivor and two aid workers said that artillery fire had been heard northwest of Dedebit in the weeks before the strike.

The attack forced the displaced Tigrayan community, victims of serious abuses by Amhara forces in late 2021, to be displaced yet again, Human Rights Watch said. By January 15, the remaining displaced people were relocated from Dedebit to Selekhleka.

The laws of war applicable to the conflict in northern Ethiopia prohibit attacks that target civilians and civilian objects, that do not or cannot discriminate between civilians and combatants, or that are expected to cause harm to civilians or civilian property that is disproportionate to any anticipated military advantage.

The laws of war require parties to the conflict to distinguish at all times between civilian objects and military objectives, and attacking forces must do everything feasible to verify that targets are military objectives. If there is doubt as to whether an object normally dedicated to civilian purposes, such as a school, is being used for military purposes, it shall be presumed not to be so.

Violations of the laws of war committed with criminal intent, that is deliberately or recklessly, are war crimes. The repeated unlawful strikes on the school compound at Dedebit, in which there were no evident military targets, strongly suggest that the attack was deliberate.

“The horrific airstrike on a school packed with displaced people reflects a broader failing by the Ethiopian government to ensure compliance with the laws of war and minimize civilian harm,” Bader said. “This unlawful attack should be a reminder to governments selling arms to the warring parties that they too can be found complicit for foreseeable war crimes.”

For more information on the strike on Dedebit, please see below.

Establishment of the Dedebit Displaced Persons’ Camp

In November and December, Amhara security forces renewed abuses, including mass detentions and killings, against Tigrayans remaining in the Western Tigray towns of Adebai, Humera, and Rawyan, that were controlled by Amhara forces and administrators. The security forces expelled thousands, including many older people, pregnant women, and women with children. They started to arrive in northwestern Tigray in mid-November, including in the small town of Dedebit.

A November 24 humanitarian assessment registered 3,463 displaced people in Dedebit, mainly coming from Humera and its surrounding area. By December 15, UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, reported that 29,000 people had arrived from Western Tigray in the northwestern Zone, including 4,000 in Dedebit.

Satellite imagery recorded in early December confirmed the influx. Crowds are visible on satellite imagery inside the school compound, as well as along the primary road that connects Dedebit with Shire, and at its Thursday market. By January 1, dozens of tents and plastic sheets are newly visible on a satellite image, mainly west of school buildings next to the barbed wire fencing and the main gate and under the trees.

January 7 Attacks

On the night of January 7, three munitions hit the Dedebit elementary school compound. A man sheltering near one of the impact sites said the first two explosions were at most 30 seconds apart and the third was a minute later:

After the first strike, it was impossible for me to identify anything. My 9-year-olddaughter came close to me and cuddled me, because of fear. I couldn’t see my wife but realized later she had been hit. I could see bodies here and there, bodies and clothes on trees. It was so difficult to understand what was happening at that time.

In the morning, the displaced and others came and collect[ed] the bodies and buried them on that day, that’s when I could see the devastation.

The man’s wife was injured in the strike.

A video recorded by Tigrai TV, a Tigray regional state media, and shared on Facebook of the attack’s aftermath shows at least 29 bodies, including 8 women and 8 children, lined up near school buildings. Some appeared to have crushed limbs, or profound blast and fragmentation wounds, and some bodies had been blown apart.

The survivor said that many bodies were unrecognizable. An aid worker who traveled to the site on January 8 said, “It’s not possible to say the exact number…. There were body parts from the damage site … There were dead in the school.… [F]or some households, everyone was dead.” The victims were reportedly buried in a mass grave in Dedebit.

Two medical officials described treating civilians with abdominal trauma, destroyed limbs, and other more minor injuries at the hospital in Shire.

A doctor said 46 of the wounded were brought to Shire’s Sihul hospital, including one child who was dead on arrival and three other people who later died, including a 70-year-old man who had abdominal trauma. The doctor said he performed two amputations, including amputating a boy’s right hand. Two doctors noted that the wounded also suffered from malnutrition, including anemia.

Satellite imagery, photos, and testimony indicate that the detonation of one munition caused significant damage to the roof and north façade of the school buildings in which dozens of civilians were sleeping, and at least two other impact sites. The blast damage at each of the three impact sites indicates a high-pressure blastwave that damages walls, roofs, and vegetation.

Eleven photos sent to Human Rights Watch by humanitarian workers who visited the school on January 13, as well as several videos uploaded to YouTube by Tigrai TV, provided additional detail on the strike damage.

Three aid workers and a medical professional who visited the school following the attacks identified two additional impact sites where munitions detonated and destroyed the tents and plastic sheets in the schoolyard. They said they saw human flesh and blood around these two locations.

Thirteen images of an impact site near the main gate sent by the aid workers show clothing, the remnants of tents, and human flesh scattered across the ground and trees.

The man who had been sheltering near that impact site, near the gate under some trees, said: “My wife’s left eye was hit by the strike, she lost her left eye. She still has some fragments in her left hand.”

At the third impact site, further north along the schoolyard fence, multiple videos uploaded to YouTube by Tigrai TV show piles of debris and clothing. Six images sent by aid workers show human flesh hanging from trees along the fence.

The survivor said that three entire families had been killed in the attack: “I heard that a family of 8, and a mother and child, 10 individuals, all of them were killed. And another neighbor, a family of 4, all killed. Then another family of 2 were all killed.”

On January 9, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) announced that aid agencies had temporarily suspended their activities in the area due to ongoing threats of drone strikes. Satellite imagery collected one week after the strike, on January 14, doesn’t show tents in the school compound. By January 15, the surviving displaced people had all been relocated to Selekhleka, 30 kilometers from Shire. UNHCR said it was providing 1,000 units of plastic sheeting and help with transporting the surviving community members there. However, on February 22, an aid worker said that fuel shortages were preventing humanitarian agencies from reaching Selekhleka.

The survivor expressed his concerns for the future:

We still need to survive in the meantime, but as it stands, we have no education, no livelihood, and we are being attacked. We need essential humanitarian assistance. Without this, we won’t survive. Everyone has to facilitate [this].

Weapon Used in the Strike

Human Rights Watch assessed photos of remnants collected by displaced people and aid workers. Photos of guidance fins and body fixtures unique to the MAM-L allowed positive identification of the weapon.

The MAM-L guided bomb is a very accurate 22-kilogram weapon that is targeted by a laser beam and is most often dropped from the TB-2 armed drone, which can carry up to four MAM-L guided bombs and the necessary targeting system. The TB-2 drone is manufactured by Turkish company Baykar Defence. This munition can also be used by light aircraft, but the aircraft requires a laser designator/targeting system. Three known warhead variants are advertised by Roketsan, its Turkey-based manufacturer: tandem warhead high-explosive anti-tank, blast fragmentation, and enhanced blast (also called a thermobaric weapon).

According to publicly available technical sources, the weight of the warheads used by the MAM-L guided bomb is in the range of 8 to 10 kilograms. The guidance fins recovered at the site are of a unique configuration common to the three known variants of the MAM-L guided bomb.

The civilian protection organization, Pax, which has been tracking the presence of drones throughout the northern Ethiopia conflict, identified a Turkish-made TB-2 drone stationed at an Ethiopian airbase, Harar Meda.

The types of injuries found in the strike victims were entirely consistent with those created by an enhanced blast weapon, including profound blast injuries, crushed limbs, total body disruption, and small irregular fragmentation wounds, Human Rights Watch said.

Enhanced blast weapons kill or injure in three ways: with the blast wave; with flying debris or collapsing buildings; and by the blast wind throwing bodies against the ground, equipment, structures, and other stationary objects. Enhanced blast weapons are designed to kill and damage over a wide area and have particularly devastating effect in closed spaces. As a result, they are prone to indiscriminate use, especially in or near populated areas. In urban settings it is very difficult to limit the effect of enhanced blast weapons to combatants, and the nature of enhanced blast weapons makes it virtually impossible for civilians to take shelter from their destructive effect.

Recommendations

- The Ethiopian federal government should credibly and impartially investigate the attack on Dedebit and fairly prosecute those found responsible for war crimes. It should also facilitate an independent investigation of the attack by impartial international monitors and make public findings into the harm drone strikes have caused to civilians throughout the conflict, including disaggregated data on civilian harm.

- The government should facilitate investigations of the conflict in Ethiopia by the International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ commission of inquiry, and immediately allow humanitarian access and lift restrictions on basic services to Tigray. Ethiopia should also endorse and implement the Safe Schools Declaration, to discourage the use of schools by the warring parties.

- All warring parties should respect international humanitarian law, immediately prevent, and stop unlawful attacks against civilians, and facilitate unhindered humanitarian access in areas under their control.

- Countries selling or transferring arms, ammunition, or military equipment to Ethiopia or other parties to the conflict in northern Ethiopia should cease doing so until the party takes significant measures to address impunity for laws of war violations.

- The UN Security Council should add Ethiopia to its formal agenda and impose targeted individual sanctions against those most responsible for violations of international human rights and humanitarian law, including against individuals deliberately hindering the delivery of aid, and impose a global embargo on the sale and supply of arms, ammunition, and military equipment, to all warring parties in Ethiopia’s northern conflict.

- The UN secretary-general should add Ethiopia as a “situation of concern” in his 2022 annual report on children and armed conflict in light of grave violations committed against children, including the killing and maiming of children, and attacks on schools.